"Design is too complex for one liners." Bertjan Pot

When I met Bertjan Pot for the first time last year at Moooi's Unexpected Welcome extravaganza in Tortona, I had kept him waiting for more than half an hour due to a misunderstanding with the interview times. Instead of receiving a cold and unresponsive interview in retaliation for my lateness, Pot chatted away for over an hour. With typical good humour and humility Bertjan Pot laughed at how small his first solo show was. “My first solo exhibition anywhere in the world was in Sydney with Sarah King at The School's Gallery Oh. The entire exhibition was just one of my masks - but it was just me on show"! Here is a transcript of the interview that shows that not all Dutch design is serious and conceptual - some of it is just for fun.

Q: How did your masks come about?

A: Sometimes I start the day with making a mask. The nice thing about the masks is that I get a lot of feedback from people who have seen them, telling me that I should look at the masks of different traditional groups like the Inuit or the tribes of New Guinea or some other primitive group. So it’s great that they have created such an enthusiastic response. My technique for making the masks is pretty primitive. It’s really just me taking some yarn and rope and stitching them together on the sewing machine. If you don’t have a n injection moulding machine and you have to use primitive means to create what you wan to make – just like the people in Africa or New Zealand or wherever. You know the Inuit only had what was washed up on the shore because there are no trees growing there so if they needed wood they have to search and find it.

If you have these sorts of restrictions then you get primitive results. In a way my masks are just a clumsy, primitive technique and they just turn out that way. If I make a mask they invariably look African because it’s about primitive means.

I once made a model of an interior that I had designed and I wanted a little rug to go in the model, along with a model sofa and so forth, so I set about making one. I work a lot with wooden models that I make in a scale of 1 : 10. I tried to just cut a piece of fabric in the right sort of size and shape but it didn’t work so I started stitching some fine rope together and it looked really cool as a carpet. I still had that sample a few years later and I had a lot of rope left over from a rope sofa I made for the Tilburg Textile Museum, so I decided I’d try to make a very big carpet using the same technique. It wasn’t working because it wouldn’t stay flat - rising up in the centre so I decided to quit when it was still just a couple of feet across. Just then my assistant came along and said - “Oh, that would make a brilliant mask” and that was it. From then on I’ve been making masks when the mood strikes me.

Q: How did you come to be into sewing?

A: When I was fourteen I used to make a lot of kites and I had a kite buggy. And to save money I used to make my kites myself - well at first I got my mother to sew them until one day she got fed up with that and told me to make my own! So I learnt to sew and still really like the technique.

Q: It’s interesting that you like these crafty techniques but are able to design quite hi tech things too – like the ‘Heracleum’ light for Moooi.

A: Well actually the hi tech part was all Marcel Wanders. I just developed the shape. I had this idea of where a bundle of stick-like branches are split then split again ending up like leaves on the end of a branch. Marcel investigated that concept but at a certain point the soldering cost to join all the wiring together would get so high that it wouldn’t be feasible. So a while later Marcel came to the studio to the studio to talk about the project and by the end of him describing what the problems were with the design as it existed I knew exactly what he was intending to do to resolve the problem - dip it in two layers of metal that would conduct the electricity to power the lights at the end - this way there was no wiring so it looked better and was possible to produce for a reasonable cost. He developed his patented LED sandwich technology for the light and he now has his own light that uses this same technique; the ‘Ink’ chandelier. I don’t see it as hi-tech - it doesn’t use any microchips or anything like that. I think it’s just clever.

Q: Where did your fascination with fabric come from?

A: I have a new product - a light that is made on a Jacquard machine. Jacquard has been around for a long time - normally it's controlled by cards with holes in them - sort of like early computer programs and the fabric has a mirror image of one design to make up the fabric’s full width. But with this particular machine every thread on the loom is connected to a servomotor and is programmed by a computer. So every one of the 3600 and something threads can be pulled up or down while weaving. It’s the same machine we use to create the ‘Font of the Loom’ products. It’s double weaving and I first got fascinated by this technique when my partner bought a scarf in Japan that was mostly grey but went to white and to black in parts without any joins. It was all woven on the same machine at the same time so I had to research into how this was possible.

With the light, what is really interesting is that we have to weave two very different fabrics at the same time in to this pocket shape. Three colours of yarn go in - one is a thick white, one is silver and one is a thin white. The top fabric layer is thick white on the top but silver on the bottom to reflect the light and the thin white forms the bottom of the pocket. But the beauty of the weave is that you don’t have to sew the edges together or glue anything - it’s all woven into the final shape with the right combination of reflective silver interior and a white exterior. At one point we were doing quadruple weaves like tunnels and things like that but in the end it all got too complicated and it seemed better just to produce one pocket with everything in there.

Q: How do you approach proportion?

A: Every material has it’s own ‘right’ appearance. For me the technique often comes first then the appearance comes later, so that depending on the technique it could end up big fat and blobby or thin and fragile. I like both! I did the ‘Slim' table with Dutch brand Arco, then five years later we did the ‘Fat’ table because it was an exploration of the opposite concept. When we did the ‘Slim’ table I approached Arco with the idea that rather than make a really thin table in wood where the table needs to be reinforced with steel, why not just veneer the steel directly. So Arco did some research and came back with a cardboard honeycomb material inside steel sheet that they could then veneer with real timber. It was super strong but only 20 mm thick and could be 3.6 metres long with just four very slim legs at each corner. It was Arco who solved the problem I just planted the seed.

Q: Your early success came through the use of resin and fiber in the ‘Random’ light and the ‘Carbon’ chair, are you tempted to do more in that material?

A: Once in a while I still think about doing something because I still have all those materials in my studio and carbon fiber is really quite scarce now. It’s actually a very nice and simple technique but on the other hand I wouldn’t start with composites in that way again because of their environmental impact. For the chairs that are already out there it’s fine and I hope people never throw them out but I don’t know that I would accept a commission in carbon fiber or fiberglass these days because it’s non-recyclable. But in regards to those early products of mine, I did them myself because I didn’t have factories that wanted to work with me at that stage and so now I’m more likely to use bio resins and do things with a producer. When I was exploring carbon fiber in the early 2000’s, I had designed the ‘Random chair’ - a low lounge chair - then I wanted to see whether it would work as a dining chair on a high base, so rather than design something myself, I just copied the Eames 'Eiffel' tower base as a test. There were only two of those chairs ever made. I think I just liked the opportunity to give it a funny name - ‘Carbon copy’. They were bought by a museum and I have never had any complaints from the Eames family. After I knew it would work in this form I designed a new base and the chair was put into production by Moooi. You can’t actually copy metal in carbon fiber anyway as the material needs to use different methods of connection and it ends up a different shape - you can’t cut and weld, you have to have a continuous flow of the material.

Q: You mainly work for Dutch companies. Why is that?

A: The types of products I design need regular visits to the factory for me to develop the manufacturing process, so for that reason they are all in Holland.

Even the ‘Jumper’ chair for the British company Established & Sons is made in Holland! I had a few attempts with Italian companies but I found that they felt that a designer's drawing was etched in stone - that it was a masterpiece that they had to faithfully reproduce. I don’t really work that way. I prefer a much more collaborative approach. Some designers are good at presenting a finished design that is totally resolved. I need help from others who know the manufacturing processes to get the most out of my ideas. Some of my ideas a re a bit clumsy or far-fetched and so talking it over with the manufacturer can help you find a new improved solution. I usually make my designs as 1 : 10 scale models - I don’t do a lot of sketching but I’m often asked for drawings after the fact. It’s easy to draw up something once you’ve worked it all out and make yourself look like a genius.

Q: Can you tell me a about the brand DHPH that you collaborate with?

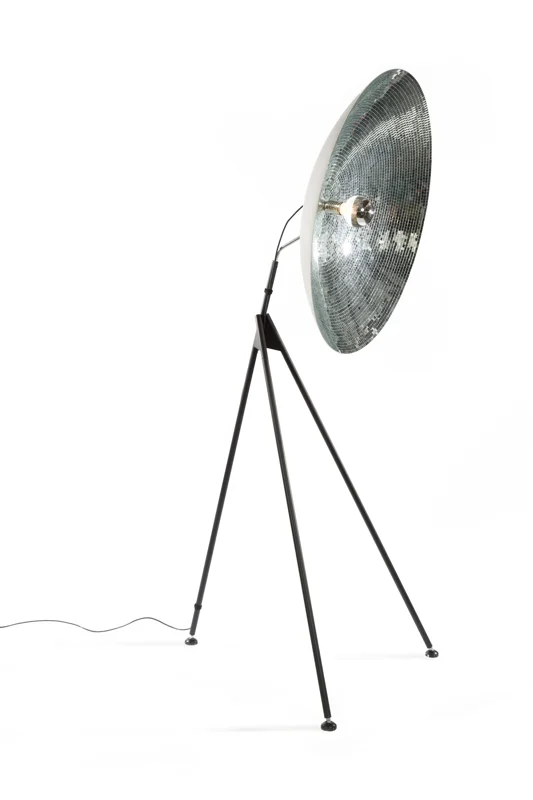

A: Well, Bas Den Herder, who is the DH in DHPH (which stands for Den Herder Production House), used to make all the stuff for Maarten Baas and Maarten used to be my neighbour in Eindhoven when I was studying there. So we go back a far way. Since 2005 the two of them have been working together under the name Baas & den Herder, with Maarten designing and Bas heading up the production of the pieces which are mostly handmade in small batches. Bas was interested in working with other designers and created DHPH in 2012 as an outlet for other things he found interesting. He had seen the ladder light I did for a restaurant near where I live. Originally there were just four that I made myself – just for this restaurant. The ‘Downstairs Light’ as it’s now called is basically hand made - we buy in a particular aluminium ladder and drill a lot of holes in it and fit a lot of LED lights. I enjoy talking with Bas and mulling over what his company should be like - its product placement and how it is presented in Milan and so forth. I’m not the art director of the brand but I’m involved in a lot of discussions with Bas about the products and the brand’s direction. I had designed a product with Moooi in mind way back in 2003 but it proved to be too expensive for them because of the amount of handwork involved. The ‘Disco Dome’ is a pendant light that uses small mirrors like on a disco ball but these are placed on the inside. DHPH re-launched it last year and this year we introduced the ‘Disco Dish’ - a floor light version using the same technique and materials.

These days disco balls are all made in China - otherwise they would be way too expensive - but we make these lights in Holland. There is a method to making them - you don’t glue the mirror pieces in individually, they are placed in strips.

Q: On your website you have divided up your projects by some interesting groupings like Tricks & Flicks, Plain & Simple , Rough & Ready, Maths & Physics and of course, Disco. Why?

A: I have regular categories too - its just an alternative way to browse the website. Grouping things by product categories is fine for some people but this method of grouping produces an interesting family of products. I think it’s more fun that people can see all our shiny and silver products in one go if they go into the Disco category!

Q: Humour seems indelibly attached to your work - do you think this is the case?

A: I like to keep it playful. For me it’s a way of being more open. If you take things to seriously it blocks out other possibilities but if you keep joking about things it’s so much more inspirational to keep the composition open. If you try to be funny in conversation it can go everywhere where if you try to be serious you end up going down one path. I don’t make jokes for jokes sake however. If the joke washes off there should still be a good product underneath.

For more information on the wild and wonderful world of Bertjan Pot, visit his website.